Sticking to the name that’s been adopted in Australia, rosé doesn’t only come in the one pink hue. Check out the rosé aisle in any bottle shop, and the wines form a colour range worthy of a Dulux chart – shades of pale copper, pastel pink, cherry red, incandescent fuchsia, mauve blushes and magenta, through to apricot and even orange. In the mix are also stylistic variations, from crisp and dry to textural and savoury, and generous and sweetish – sometimes too much so. But you wouldn’t know all that unless you crack open a bottle.

“It’s a fascinating category and one of the few that’s judged on what the wine looks like rather than how it’s made, where it’s from and what particular grape varieties are used. It’s just pink for most people,” says lauded sommelier Leanne Altmann, beverage director across Andrew McConnell’s restaurants in Melbourne.

“With that, it can be an area of discovery, or trepidation, as you don’t know what you’re going to get. I prefer restrained rosés with lovely aromatics that are savoury, but creamy and textural. As with all wines, there has to be a balance between texture and aromatics. Also, my context of wine is at the table. It’s all about the food and wine combination.”

Leanne’s current favourite is from Cotes de Provence producer Clos Cibonne, which seems to be the darling of the sommelier scene. For good reason, too. Its wines are wonderful, complex, detailed and crafted from the ancient variety tibouren. “They take their rosé seriously.” Of the local examples, she likes the full-flavoured, textural and dry Fairbank from Sutton Grange, which comes in magnums. “That’s fun at Christmas time. It’s also delicious,” she says.

Rosé wine and its grape varieties

While Australian sales of rosé continue to soar in venues and also the retail trade, it’s worth acknowledging that France’s Provence plays a key role, long regarded as the rosé capital of the world. Provence’s annual production hovers around a mind-boggling 156 million bottles of appellation wine, satisfying six per cent of the world’s demand. Importantly, 89 per cent of the grapes that grow there are dedicated to rosé – namely grenache, cinsault, shiraz, mourvedre, tibouren and even vermentino.

While drinkers might not be fussed about the grape varieties that go into their rosé, it begs the question whether they matter. For Julian Langworthy, Deep Woods Estate winemaker and rosé aficionado, they are essential. “Certain varieties impart flavours and characters that make great wine, while some don’t have the flavour profile to make what I think is quality rosé,” he says.

In Julian’s region of Margaret River, he says cabernet sauvignon

and cabernet franc just can’t get ripe enough when picked around

12.5 per cent baume. This can result in unripe, green flavours. And while grenache is one of the most common varieties used in rosé across the country, Julian says it can often make fruit-sweet styles, so he has looked elsewhere for inspiration.

“A favourite is tempranillo,” he says. “It has beautiful colour and a subtle savouriness. Another impressive variety is nebbiolo, which is crunchier, has more tannins and creates a more structured rosé.” As it happens, Deep Woods Estate Rosé is mostly tempranillo with a glug of shiraz, blended with a small amount of barrel-fermented vermentino. Julian and wife Alana also have their own label, Nocturne, with a stunning rosé made from nebbiolo.

“Our top estate rosé at Deep Woods is nuanced, fine and eminently drinkable, whereas the Nocturne demands food. It’s more phenolic with a vibrant acid structure,” Julian says. Both are classy styles, with a mere 200 dozen made of the Nocturne, while Deep Woods hovers around 1600 dozen. Such is the commitment of Deep Woods to rosé, the winery is planting another 2.4 hectares of tempranillo to meet the demand.

Rosé winemaking approaches

These wines are crafted with intent, from grapes dedicated to the style and not via the saignee method, meaning “to bleed” in French. With saignee, two wines are made – a rosé from juice pressed or bled off from the grape must in tank, leaving behind a red wine

that will be more concentrated due to the higher skin-to-juice ratio. But the bled juice can end up producing something simple and boring. Saignee is often regarded as an afterthought and even producers in Provence think it’s a cop out.

The quality angle

Winemaker Sarah Fagan of Yarra Valley’s De Bortoli also doesn’t support the saignee method. Instead, the team mostly picks for purpose, with a commitment to using the best varieties for different styles. “We have invested heavily in several rosés. We use pinot noir and nebbiolo from the Yarra Valley, grenache from Heathcote, and sangiovese out of the King Valley, and there’s more we make, too. We are showcasing a range, all with the aim of making pretty tasty and delicious, dry and textural rosés,” Sarah says. She likes grenache for its aromatics, nebbiolo for its structure and pinot noir for texture. From those three varieties, De Bortoli produces a healthy 27,000 dozen.

Unfortunately, rosé’s popularity means there is also a lot of dross being made because it’s regarded as a cash cow. And that gives the false impression that quality is not a factor at all. There are high-end wines, however, that come with price points to match.

For example, the Clos Cibonne range hovers around $45, while another excellent producer is Domaine Tempier Bandol, which sits at $65. The most expensive of all, Chateau d’Esclans Garrus, comes in at $220. In regards to Australian examples, the best tend to fall between $25 and $40.

De Bortoli has always been clever at gauging the market and making wines people like, partly by following a simple credo that Sarah describes as ‘the Steve Webber approach’, named after De Bortoli’s chief winemaker. “Steve says that with every wine we make, we have to be able to sit on the back deck and enjoy it, and tell our mates and peers how good it is. If you don’t, what’s the point? It has to be about enjoyment.”

Julian agrees. “Five years ago, rosé was purple and sweet, and now it has swung to the other side and is the palest colour, nothing more than over-fined and insipid. It really shits me. Rosé is not an excuse for alcoholic pink water. It deserves respect,” he says. “What I like about good rosé is its drinkability; its smash-ability. And there’s nothing wrong with that.”

This story first appeared in the December/January issue of Halliday magazine, complete with Jane Faulkner’s selection of 10 top rosés. Get your copy or subscribe today.

Latest Articles

-

From the tasting team

Curious, diverse, confident: Mike Bennie on Wairarapa

1 day ago -

News

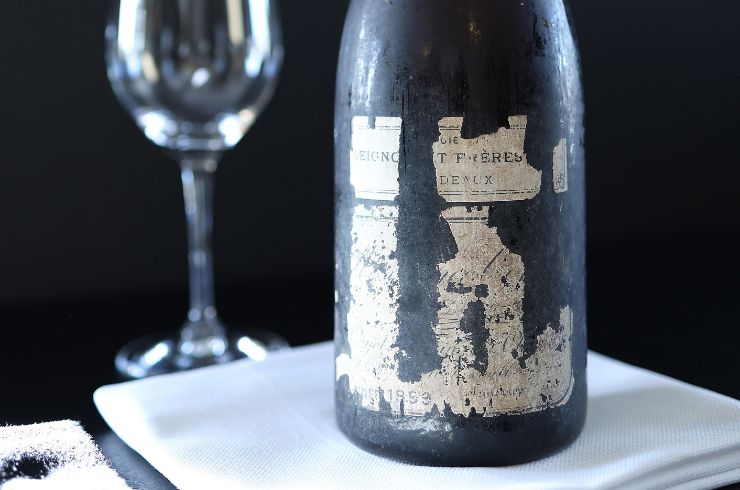

Why a co-owner of Bass Phillip decided to taste, instead of trade, this 127-year-old bottle of wine

1 day ago -

Meet the winemaker

What makes Kusuda one of New Zealand's most extraordinary producers

1 day ago -

Wine Lists

Discover New Zealand: seven highly rated wines from the Wairarapa region

2 days ago