Jancis Robinson MW once called Hunter Valley semillon “Australia’s greatest gift to the wine world”. Together with Rutherglen fortified expressions, it is certainly our only truly unique one. Hunter semillon is inimitable because of the relatively early harvest window, borne of the necessity to avoid early summer rains. This equips the variety with high acidity, lowish alcohol (10–12.5 per cent) and the capacity to achieve an apotheosis of balletic poise and toasty intensity that belies its light weight.

The orb of Hunter semillon is very different to that of its original home of Bordeaux and France’s south-west. There, later harvest windows impart moderate freshness and the grape, seldom found as a straight varietal expression, is used as a blending agent with sauvignon blanc, at times muscadelle, and is often rendered in oak.

Classic Hunter semillon is fermented cool in tank and bottled imminently to retain primary fruit and cut-glass precision. This approach, however, breeds steely, reticent wines with little to show in their youth but for verdant notes of lemongrass, citrus and lip-smacking acidity. They demand at least five-years of bottle age to reach an adolescence that barely glimpses the potential of buttered toast, glazed quince and lemon drop accents that they are capable of with middle age and beyond. While producers such as Tyrrell’s and Mount Pleasant cast certain cuvées into the market with some age up their sleeves, in a time when the vast majority of wine is consumed within 24 hours of purchase, the perennial question is ‘who’s waiting?’

In response, certain trends have emerged. These include obvious approaches to broaden the texture of the wines to make them accessible earlier, incorporating extended time on lees following fermentation and later harvest windows, accentuated by global warming and a string of drought years, finally punctuated by the cooler 2021 vintage.

Andrew Thomas’ semillons, for example, stretch into the stone and tropical flavour spectrum with recent releases. More radically, Briar Ridge’s reliance on ambient yeast, extended lees work and skin contact for their top Dairy Hill Semillon serve to soften the variety’s brittle acidity (with the potassium residing in the grape skins), while imparting a waft of creaminess, textural intrigue and umami breadth to the mid-palate.

I’ll be surprised if large format oak is not introduced moving forward, such is the wine’s brilliance. The 2021 is stellar, receiving one of my highest scores to date. Tyrrell’s, the undisputed regional leader, also seems to have relaxed their wines’ steely determination without forfeiting fidelity to place, style or capacity to cellar. The address’s single vineyard iterations are second to none.

Another point of interest is the expanding number of white wines hailing from loams and red clays, rather than the traditional option of growing semillon on meagre sandy alluvials and sedimentary grey soils.

Clay’s greater water-retention facilitates more nutrient uptake by the vine, riper grapes, lower acidities and broader wines of a more immediate appeal. Clay is also a greater reservoir of moisture in hotter years, auguring positively in the face of the challenges already upon us. While chardonnay is increasingly prevalent on the richer soils, semillon may also benefit as wines of a more imminent appeal are increasingly sought.

Tyrrells’ Steven’s Semillon, one of the estate’s top single vineyards, is such an example. When compared to its steelier Belford brethren, the latticework is looser and the textural kit more sumptuous, even at a young age.

While the Hunter is not known for chardonnay necessarily, there are some good examples. Tyrrell’s again, with the lauded Vat-47, along with Lake's Folly, has long led the way. However, Keith Tulloch’s wines, always marked by an assiduous attention to detail, should be on your radar.

The address has benefited from son Alisdair Tulloch’s growing involvement and the recent appointment of Brendan Kaczorowski as winemaker. Both of these young men have a comprehension of texture’s importance (over mere acidity) to a wine’s gait: its poise, complexity and expressiveness, gleaned from extensive experience in the Rhône. This seems to reach its apogee in the Tawarri Chardonnay, a richly flavoured wine with an interplay of gentle tension and phenolic pucker borne of red clay soils.

More exciting than chardonnay in the Hunter is fiano and albariño. The former seems to have a predilection for expressiveness and varietal fealty, even when handled innocuously as a bang-in-bang-out proposition. Conversely, this is a platform for considerable flare and optimism when the grape is handled well. Again, Briar Ridge is leading the way with a ripping expression fermented wild, embellished with plenty of lees and raised in large format wood.

Fiano is a star of the future such is its sturdy physiognomy. It is neither thirsty nor intimidated by the humid, warm conditions of the Hunter. Not surprising, given that its spiritual home is the volcanic hillsides of Avellino, inland from Naples in Italy’s Campania region. Best, it is one of the world’s great white varieties rather than a mere arriviste shoved into the fray as a fall guy (tempranillo anyone?). Briar Ridge’s example bares the textural signature of winemaker Alex Beckett, a fan of contemporary German riesling and Loire Valley chenin blanc. His fiano is all glazed quince, nashi pear and peach pith, with a pungent herbal undercarriage of wild fennel and pepper.

Even more exciting is Beckett’s deft touch with albariño. And no, I’m not talking about the faux-albariño that was mistakenly allowed to trickle onto these shores before being correctly identified as savagnin. I am speaking of the real deal, a Galiçian cultivar grown on sandy soils in a humid climate not so dissimilar to the Hunter. Beckett’s expression is possibly the single most exciting white wine I have tasted for the Wine Companion to date. At least this past year.

Fermented spontaneously in large wood with ample solids, before undergoing partial malolactic conversion, it is a cracker of a wine: apricot pith and curd unravel across a skein of juicy freshness and pixelated phenolic detail. It is a wine that strikes a European sensibility while suggesting that the Hunter is capable of so much more. Albariño’s righteousness in these parts is compounded by Ollie Margan’s version, one of the wines across his new label, Breaking Ground. Grown on sand and minimally messed with, his albariño is possibly the star of the line-up, strutting apricot pith and white pepper accents across a talcy beam of chew and freshness. Circa $20, this and the rest of the range are veritable bargains: sassy, easygoing and sophisticated all at once.

Hunter Valley red wines

While the Hunter has long been known for shiraz, there is always an outlier here and there. One that stands out, forever responsible for among the region’s very finest wines, is Lake's Folly. An impeccably kept red clay knoll, loamy and ferrous and as beautiful as any site in the Hunter. An undulation that thrums toward the Valley’s heart as one passes it on Broke Road.

A meld of cabernet and bordeaux compadres with a dollop of shiraz, Lake's Folly red is a wine that beguiles, rather than bludgeons. I often compare it to a riper version of a chinon, the Loire Valley’s great cabernet franc, so perfumed is the wine, lithe and chiffon-esque the tannins. Best, it usually clocks in at a digestible alcohol level barely nudging mid-weight.

Retrospectively, the 2019 was my favourite red wine of last year’s Companion at a mere 12.6 per cent and perfectly ripe. Clearly the site is magical, so immutable is the pedigree of the wines. Far from a trend, Lake's Folly is the institution that sets a standard that others, boldly opting for varieties other than the regional stalwarts, can look up to. Lake's is a barometer of confidence and quality.

With this in mind, Angus Vinden’s suite of young reds is impressive. 2021, a cooler year of red fruit accents is, in his hands, a joy! Vinden works with open-top concrete fermenters and an arsenal of large format wood and ceramic eggs. His ferments are spontaneous and extraction periods increasingly attenuated, utilising whole berries, a dash of bunches and gentle agitation with controlled oxidative handling over a longer period, avoiding reduction.

Yet aside from dangerously drinkable reds (one a blend of shiraz and gamay serving as a regional nod to a passetoutgrain), Vinden’s work with tempranillo is particularly impressive given the forlorn history of this fine variety in Australia. While his more traditional wines are labelled eponymously, experimental expressions including those of tempranillo are labelled under the ‘Headcase’ banner.

The Headcase Somerset Vineyard Tempranillo 2019 and its longer aged sibling, the Grand Reserve 2018, with 40 months in a combination of French and American wood, are both worthy of attention. Tempranillo’s rumble of blue fruits, lilac perfume and dusty swathe of tannins is a joy to behold, standing far above the mediocre domestic pack. It is a wine that drinks like cabernet without the stiff upper lip of tannins.

As a side note, Vinden’s chenin blanc, too, is worth checking out. While it seems incongruous that a cool climate cultivar is planted here, Angus tells me that it was already planted when he began taking the fruit. Raised in eggs with ample lees work and the perfect amount of oak, the wine is all ginger spice, tarte Tatin and slinky phenolics driving long.

Otherwise, the Margan Family’s efforts with barbera are reaping rewards. I often found earlier incarnations a bit oaky, even though Andrew assures me that the dabble with new oak was for a very short window. This said, what Australians call ‘used’ or ‘neutral’ oak is still often detectable in a finished wine. A barrel takes a long time to wear in to the point that it no longer imparts tannins or flavour compounds.

Today Margan Barbera is very impressive. Tank fermented, with a portion raised in used barriques before the components are blended, the wine is fresher than ever before. The alcohol, more digestible. The weight, medium. The dark cherry, blackberry, tar and anise amaro accents, singing. The acidity, thirst-slaking. These are wines to reach for after a day drinking shiraz, such is their effusive freshness. Equally as impressive, albeit, in a lighter frame, is son Ollie Margan’s Breaking Ground Barbera.

Fermented wild, this moreish expression sees an intuitive addition of whole bunches to tone barbera’s high acidity while imparting a weave of spicy tannin as a waft, rather than a rasp. This is intelligent craftsmanship given the variety’s natural predilection for plenty of acidity and scant tannins. It is also synergistic with what is happening in the variety’s native Piemonte. There, barbera’s alcohols are skyrocketing and acidity falling.

Producers are turning to whole-bunch and a little more oak to mitigate the structural shortfalls, or abandoning barbera altogether for the more favoured (and traditional) dolcetto. Ollie makes no additions and like his dad, he opts for a combination of tank and older oak.

Then, of course, there is the mid-weighted, savoury style that made the Hunter famous. Following a slew of Hunter River ‘burgundy’, masterfully crafted by Maurice O’Shea at McWilliams Mount Pleasant and Karl Stockhausen at Lindemans (whose 1965 Bin 3100 and Bin 3110 are considered among the finest wines ever to be made on these shores), an uncanny meld of shiraz and pinot noir became a vector of greatness.

The 3100 was tacitly injected with around 10 per cent pinot noir to achieve the digestible, earthy style that has since come to define the region. Had Len Evans not queried the blend, however, pinot noir’s presence would never have been brought to public attention. The point is, before I waffle on any further, the Hunter was never about big, glossy red wines. This period of craftsmanship established what the region does best. And so it remains today to the point where the revival of a lighter, more drinkable idiom represents a renaissance. An epiphany. A fulcrum point. And ironically, a trend.

After all, for years Australian producers chased points from influential American commentators. When Australia’s fine wine reputation was diminished by wines of greater bombast, higher prices and poor cellar-ability from the late 1990s to early 2000s, at least among the then ‘new wave’, some producers persisted with extract and oak even if the wines were sold only on Australian shores. 2014, a brilliant vintage in the Hunter, saw the amount of oak thrown at the wines reach a giddy climax.

That vintage served as a moment of hubris that many producers tell me they now regret. The potential of the year was too often scuttled by a blindness, avarice and overly ambitious winemaking.

Seldom does one experience these sorts of wines anymore. This said, in my view the region is bifurcated stylistically. While my recent tasting for the Companion strongly indicated a paradigm shift back toward the mid-weighted Hunter River ‘burgundy’ style (not necessarily, mind you, with pinot noir as part of the blend), some producers continue to lean heavily on a reductive approach to make their wines glossy and of imminent appeal: vivid purple hues, floral aromas and taut mid-palates defined by iodine and purple fruits.

These wines are salubrious, delicious at times and tend to do well in wine shows for obvious reasons. De Iuliis, Leogate and Thomas lead the idiom, although Thomas’ wines have been stepped back, positioning themselves as modern, albeit, with a glimpse of Hunter classicism.

Tyrrell’s is leading the return to a welcome classicism. The top reds are articulated with concrete, large format wood and longer, more gentle agitations, increasingly with whole berries in the mix. The family’s vaunted dry grown sites and their respective cuvées, 4 Acres, Johnno’s, Old Patch and 8 Acres, are spellbinding wines that epitomise all that the Hunter (and only the Hunter) does so well, inimitable with its scents of sweet earth, terracotta and bright red fruits.

Each expression, too, fidelitous to varying geologies, expressed as textural nuances blaring real points of difference across cuvées (rather than plots of a vineyard expanse that are carved out and called ‘Single Vineyard’ for the sake of PR purposes).

Others making outstanding shiraz include Briar Ridge, Brokenwood, Audrey Wilkinson, Keith Tulloch, Vinden, Glenguin Estate and Glandore. Mount Pleasant, too, after years of very reductive winemaking seem to have swung the pendulum back toward the classic mold. Their Mountain series of ‘Dry Red’ wines, the 1921 Vines Old Paddock and Rosehill Shiraz among others, are beautiful wines. The tannic latticework is firm, fibrous and impeccably architected.

While some of these makers are young, they are travelled, well versed in the great wines of Europe and acknowledge what their forebears in the Hunter did so well. They are forging their own paths, while respecting the Hunter patrimony and the style that it has come to define.

Latest Articles

-

From the tasting team

Curious, diverse, confident: Mike Bennie on Wairarapa

1 day ago -

News

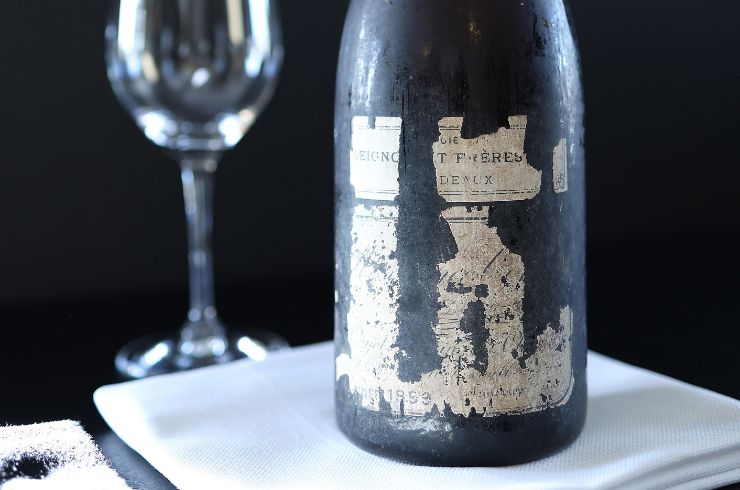

Why a co-owner of Bass Phillip decided to taste, instead of trade, this 127-year-old bottle of wine

1 day ago -

Meet the winemaker

What makes Kusuda one of New Zealand's most extraordinary producers

1 day ago -

Wine Lists

Discover New Zealand: seven highly rated wines from the Wairarapa region

2 days ago